Fotografieren verboten!

Guy Robertson

Welminski’s drawings are an intimate reflection of the artist’s approaches to history, philosophy and creativity.

6 - 31 August

Summerhall (Venue 26)

1 Summerhall,

Edinburgh EH9 1PL

Having lived and worked in Poland, since 1973 as a member of Tadeusz Kantor’s Cricot 2 theatre company and in close relationship with the Foksal Gallery, Welminski continues to make pictures and direct students in the ways and methods of Cricot 2.

The work addresses the history of his native country, particularly in relation to the censorship and devastation inflicted on its people and culture by Nazi and Soviet occupation. In the process of addressing these specific concerns, however, Welminski’s art evokes universal themes about life and death, entrapment and escape, and our relationship to individual and collective histories.

Funding for this exhibition has been kindly given by the Polish Cultural Institute and the Anna Mahler International Association.

The title of the exhibition emerges from a performance, “Da lieht der Hung begraben” [There lies the rub], which Andrzej and Teresa Welminski developed with a group of German actors at the Stuttgart Theater De Rampe in 1997, as part of their efforts to share the ideas of Cricot 2 after Kantor’s death in 1990.

In a hallucinogenic turning of the pages of time, the performance addressed shared German and Polish history from their mythical Nibelung origins to modern times, culminating in a scene from a concentration camp in which a model of a stag appears with a sign, commonly found in concentration camps, reading: “Photography is strictly forbidden. Photographers will be shot without warning.”

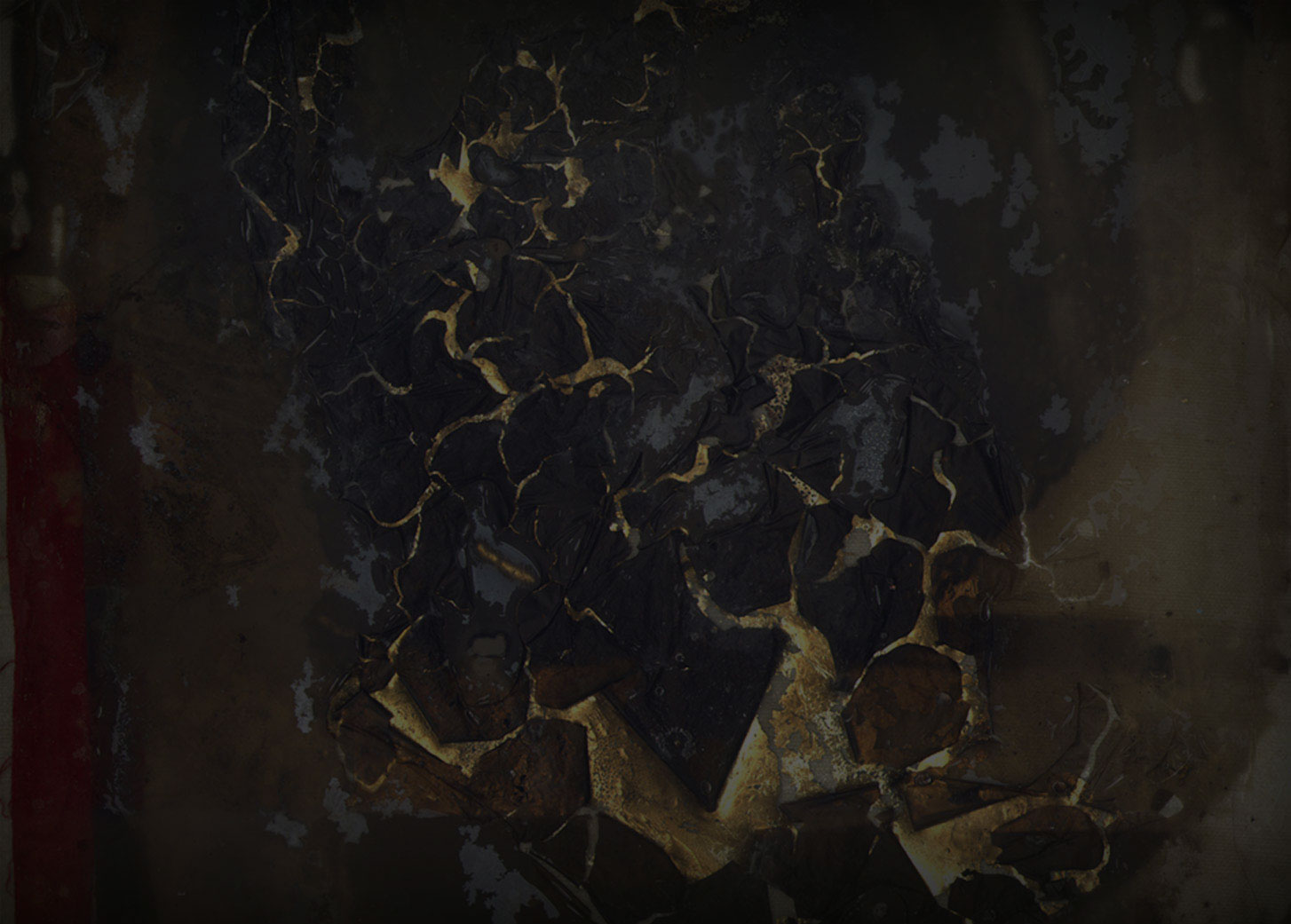

Welminski has for many years engaged with the camera as a means and metaphor for ways of remembering and creating: for exploring ideas about control of the mind and history. In Kantor’s The Dead Class Welminski played a photographer with a five metre long billows camera which the artist had carefully replicated. The object in this exhibition, a receptacle on a stool with gas taps, takes on direct relationships both with a camera and with gas chambers in concentration camps. Welminski also used this object as an alchemical device: putting drawings inside and flushing liquids through it to affect the surfaces. With the ‘In Ruins’ series he develops parts of photographs on found paper and paints with photo-sensitive emulsion, allowing it to congeal in wells and cracks in the page. Elsewhere, in line-drawings, figures appear and dissipate like half-formed prints made in a darkroom. By its nature photography gives a sense of permanence – of its ability to put a stamp on time and memory. Welminski’s use of photographic techniques, therefore, coupled with the emotional directness of drawing, upsets this permanence and accepts instead a more realistic reality: one in touch with cycles of life and death and of the present as represented by complex and layered combinations of the past, indescribable by a straight photograph.

His subjects are too various and complex to give due credit to in a short text. Each, however, has a symbolic power, appealing to universal concerns, which must be opened up by the viewer. Many relate to an ongoing struggle against oppression or danger from unknown forces: children at play with a paper stove, the stag as an honorable victim and the wind-up painter as a comment on freedom of expression, to name several examples. The 20th Century history of Polish culture attests to terrible censorship and destruction: in the genocides thousands of intellectuals, artists and academics were sought out and killed. Books were burnt, the press gagged, entertainment banned, art was destroyed or seized in an effort to wipe out Polish identity. The title of the exhibition, then, Fotografieren verboten!, draws attention to this history whilst using the theme of dispossession as a springboard for the development of new thoughts and ideas about our current situation.